- The long-term impact of the Affordable Care Act won't be measured for years

- There are still many variables that will determine the law's success or failure

- One expert says it will all come down to whether lower premiums are delivered

- Deductibles and customer satisfaction will also play into perception of whether it works

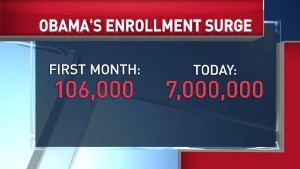

Washington (CNN) -- Sure, President Barack Obama claimed victory when he announced from the Rose Garden that more than 7 million people had signed up for Obamacare.

"No, the Affordable Care Act hasn't completely fixed our long-broken health care system, but this law has made our health care system a lot better -- a lot better," he said Tuesday, the day after enrollment closed for the year. "And that's something to be proud of."

The Democratic National Committee emailed reporters enticing them to click on a video to watch "coverage about how the Affordable Care Act is succeeding."

No doubt, Obamacare will have an impact on the immediate future of health care.

It's fair to say that more people have health insurance, whether that's because of premium subsidies or prohibitions against discrimination against preexisting conditions or the fact that those under 26 can stay on their parents' health insurance or from the expansion of Medicaid.

And the Democratic victory lap is welcome for a party suffocating under the weight of Obamacare politics, including fallout from glitches with the federal health care website and canceled insurance plans.

'One Last Thing': Obamacare

'One Last Thing': Obamacare  President Obama: Obamacare is working

President Obama: Obamacare is working  Obamacare game changer for White House?

Obamacare game changer for White House? Now that it's implemented, public opinion of the law is going to be tied to its success or failure. And the first year enrollment figures are only one small indicator.

In other words, the Obama administration's celebration might be legitimate, but it could be premature as the long-term viability of the Affordable Care Act unfolds.

Obamacare hits enrollment goal with 7.1 million sign-ups

'The real test is still to come'

There's a lot more to the story that begins with Obama's aim to reduce the ranks of the uninsured.

"The real test is still to come," said Drew Altman, president of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

And like any business, the cost and customer satisfaction are going to make or break the law and will ultimately determine enrollment.

Elaine Kamarck, a senior fellow with the Brookings Institution, said that if people can't afford to pay their monthly premiums, even with the help of government subsidies, then the law will collapse.

"Essentially, it's all going to be about the cost of the premiums," she said.

Health Secretary Kathleen Sebelius predicted recently that premiums would rise, but at a lower rate than recent history.

Sebelius thanks staff, warns work is far from over

The first clue as to whether that's true will come sometime over the summer, when insurance companies begin submitting their rates for 2015.

W.H. reports a surge in enrollment

W.H. reports a surge in enrollment  W.H. reports a surge in enrollment

W.H. reports a surge in enrollment  W.H. reports a surge in enrollment

W.H. reports a surge in enrollment "When insurers set their premiums for 2014, many of them built in some padding, assuming they were going to get an older sicker pool of enrollees," Levitt said. "When they set their premiums for 2015, they'll be looking at who actually signed up compared to what they expected."

If premiums go up, it will signal insurance companies feel the customers who've enrolled are sicker -- and thus more expensive -- than expected. But if premiums stay steady or even go down, it will show that the initial pool of customers met their expectations.

Altman says there's another cost factor -- the cost of the deductible. If people can afford the cost of the premium but their deductible is so high that they can't afford to pay for their doctors' visits, then people will give up on the law.

And customer satisfaction matters, too. If people are frustrated their doctor is no longer available in their coverage plan and they can't get the services they think they need, that could persuade them that it's more worth it to pay the tax penalty for not being insured.

Growing pains

Other government programs that are now institutions saw their share of troubles in infancy.

A New York Times story from 1996 opened with this: "Medicaid, the little understood relative of Medicare that provides benefits for needy persons who cannot get Medicare, is having trouble persuading state governments to join up."

The story noted that in Kentucky, 12,000 of the eligible 100,000 signed up. Another article in The Times said only 200,000 of an eligible 2 million people nationwide signed up for Medicaid in its first few months.

The Children's Health Insurance Program created in the 1990s also had growing pains. States used less than 20% of federal funds granted to them for the health insurance program for low-income children.

And a 1999 Times story quoted a health care expert saying it was unclear whether the number of uninsured has been reduced with CHIP.

More than a decade later, more than 7 million children receive health benefits through CHIP and every senior over the age of 65 has access to Medicare and more than 66 million people were enrolled in Medicaid in 2010 -- a number that has increased with the expansion of Medicaid in Obamacare.

What's next for Obamacare?

But Altman says Obamcare can't really be compared to other programs because the number of people who benefit from other government health programs are more uniform: Medicare benefits seniors, Medicaid the poor, CHIP is for children.

The Affordable Care Act is so varied, depending on what state you live in and what sort of coverage rules and cost framework is applied.

He notes that more than 500 different insurance zones exist around the country, each one impacting consumers differently, so anger in states where costs are high or the governor chose not to expand Medicaid might be at a different level in a state where costs are low.

As with any major piece of legislation, the law could still be changed. But politics will determine how much. If Democrats maintain control of at least one branch of government, then it would likely be tinkered with. If Republicans, however, win back the Senate and the White House in 2016, major changes could come.

While Karmack said Republicans are "going to have a hard time repealing the entire act because pieces of it are extremely popular," one way to essentially gut the law is to reduce the amount of subsidies that participants receive for their premiums.

If the subsides don't keep pace with the cost of the premiums, then the law will likely be unpopular and the ranks of the uninsured are likely to again rise.