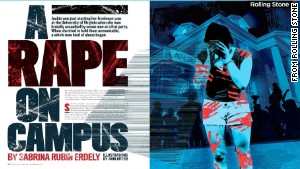

- A Rolling Stone story about a reported gang rape roiled the University of Virginia

- That sparked weeks of turmoil on campus

- The magazine later admitted flaws with the story

Charlottesville, Virginia (CNN) -- The University of Virginia school year began with a terribly sad story.

The disappearance of one of its most vulnerable — a student embarking on the rest of her life -- rocked the campus and attracted national news coverage.

Investigators say a man they have now connected to several heinous crimes against women abducted and killed Hannah Graham, an 18-year-old accomplished athlete and straight-A student. Her death sucked the carefree joy out of college life, especially for those who had just arrived for their first term.

The crime was a blunt reminder that campus is not a utopia of safety. It began a change in late-night behavior on and near campus -- the grounds, as they are called here. Some students said they started looking out for each other a bit more, checking to make sure friends got home safe.

New questions arise in UVA rape story

New questions arise in UVA rape story  Campus rape accusations and civil rights

Campus rape accusations and civil rights  Student council pres.: I believe Jackie

Student council pres.: I believe Jackie  Greek System Wants UVA Apology

Greek System Wants UVA Apology So a few weeks later, on November 19, emotions were still raw on campus when Rolling Stone published a lengthy piece detailing the brutal gang rape of a woman on campus. It portrayed the university as cold, tolerant of awful behavior -- certainly not safe for women.

National news crews descended on the university again, but things were different this time. This story did not bring the community together, as had Graham's disappearance and death. This story divided the campus, as can happen when something catches a group of people and their way of life off guard.

Bombshell article rocks campus

On an unusually warm day in late November, the campus seemed unusually solemn.

There were no impromptu quad sport pickup games in sight, even though almost everyone was in shorts.

The most noise on the quaint and historic grounds came from a protests on the steps of the main administration building, where students held signs with slogans such as "She trusted you to do the right thing" and "UVrApe." Inside, the university's governing board discussed what to do in light of the damning Rolling Stone story.

At a bagel shop around the corner, the story dominated a quiet conversation among three young women -- one defensive, one unsure and a third, silent.

"This will blow over in two weeks," one said.

Some at the bagel shop bristled at the idea that their university posed more danger to women than any other college.

"The article made it seem like it was a UVA-only problem and that people were accepting of it," said Sam Mirzai, a first-year who had just finished eating breakfast with a friend. "I think that's blatantly untrue."

Others said they felt the university had for too long ignored an obvious problem by never expelling a single student for assault, even when they admitted to it. Graffiti showed up near Rugby Road, where the fraternity houses are. A concrete barrier reads "Save the party, end rape." Someone vandalized the fraternity house of Phi Kappa Psi, where the allegedly gang rape purportedly happened.

The university administration reacted to the article swiftly.

First, the university suspended Greek life for the rest of the semester. Suddenly there were no more fraternity parties on Friday and Saturday night. The college demanded that police investigate.

University President Teresa Sullivan announced a zero-tolerance policy toward sexual assault.

"There's a piece of our culture that is broken and I ask you to come together as a strong and resilient community and to fix it," she said.

As students moved into Thanksgiving break, it seemed like things might calm down. Police worked their case. Advocates on campus were grateful for attention they felt was long overdue. Students studied for final exams and got ready for a break after the tumultuous semester.

Rolling Stone alters apology for story

Rolling Stone alters apology for story  Rolling Stone editors reviewing mistakes

Rolling Stone editors reviewing mistakes  Is 'Rolling Stone' blaming rape victim?

Is 'Rolling Stone' blaming rape victim? Then Rolling Stone shocked everyone -- again.

The ripple effects of sloppy journalism

Two weeks after publishing the chilling account of a student's rape in a fraternity house, Rolling Stone apologized under pressure from the Washington Post, which was scrutinizing its reporting methods.

The magazine admitted that its writer had not contacted the man who allegedly orchestrated the attack on Jackie -- the woman who said she was assaulted. It said the writer didn't contact any of the men that Jackie claimed participated in the attack for fear that they would retaliate against her.

"In the face of new information, there now appear to be discrepancies in Jackie's account, and we have come to the conclusion that our trust in her was misplaced," Rolling Stone said.

That last line -- "our trust in her was misplaced" -- sparked complaints that Rolling Stone was blaming the victim. The magazine amended its apology to say this: "These mistakes are on Rolling Stone, not on Jackie."

Advocates for victims of sexual violence feared that inaccuracies in one woman's story would taint the credibility of all sexual assault victims, that it would make it harder than it already is for victims to come forward.

"Honestly I was terrified when I first heard the news," said Ashley Brown, president of the campus survivor's group, OneLess. She said she feared this would set back the cause "30 years."

Those fears reverberated across the country.

"I've had a lot of our members, especially sexual assault survivors, emailing me, asking if this is going to distract from the broader, bigger problem of sexual assault on campus," said Monika Johnson-Hostler, president of the National Alliance to End Sexual Violence. "They're worried that fallout from one story is going to give people a reason to believe campus sexual assault isn't a real problem or it's been over-hyped."

Jackie's supporters noted that victims sometimes don't remember things in linear terms, that details sometimes come back in pieces.

The fraternity at the center of the storm, meanwhile, fought back with its own set of facts.

It said that the man Jackie claimed had lured her to a dark room was never a member of the frat. Phi Kappa Psi also cited records showing it did not have a party on the night Jackie says several men attacked her. And the fraternity said its house doesn't have a side staircase -- important because Jackie described descending such a staircase as she left, bloodied and broken.

"It's not part of our culture. It's just not true," said Phi Psi's attorney, Ben Warthen, of the allegations.

Yet the university administration did not budge when national Greek groups demanded an apology for shutting down fraternity activities.

And a university council that governs Greek life calmed the fears of some advocates with a pledge to remain focused on the very real problem of campus of sexual assault.

"We remain committed to being leaders in the campaign for long-term change," its statement said. "We ask that our community does not become mired in the details of one specific incident..."

Opinion: Rape culture? It's too real

Dredging up painful memories

The attention surrounding the Rolling Stone story dredged up painful memories for some women who say they were not at all surprised by the tone of the original piece.

Lyra Bartell recalled a friend who she said took advantage of her while she was drunk and upset a few years ago. She reported it to the university, asking for a no-contact order and then a formal campus investigation.

"I was having panic attacks on campus. I was literally covering my face with a hood and running from class to class because I was so fearful of running into the person who had hurt me," she said.

Then, she lost all of her friends, who sided with the accused instead of her.

Bartell graduated in May but drove back to Charlottesville at night after the Rolling Stone story. She asked students and others to write messages of support to rape survivors on a white board -- and more than 200 did in just a few days.

She recalled friends who believed someone had given them a date-rape drug.

"I remember having girlfriends roofied in frats and we would carry them out, and it was just another Friday night," she said. "People use words like, 'Oh, that's the rape-y frat.'"

Another student, Emily Powell, said friends doubted her after she said a man assaulted her during her third year on campus.

"I was really sick. I was vomiting. I felt horrible whenever I stood," she said. "I asked ... a friend of the person who had assaulted me to take me to the hospital because she had a car. And she told me that she would take me in a week, once I had calmed down, which very much felt to me like, you know, she thought I was making this up."

Later, when Powell mentioned she might file a police report, "they (friends) threatened that they would tell the police that I was — obsessed with the idea of rape and that — I would accuse anyone of rape, and they would say that I was mentally unstable."

All but one of a handful of people who told CNN they were sexually assaulted at UVA did not report the assault to the university. Bartell did. She said she dropped her case after getting an apology from the man she accused.

They all said the process is long and stressful. They also said it requires a woman to tell her story several times, including to fellow students, a prospect that made them nervous; a U.S. Senate report on campus sexual assault recommends against having students help adjudicate sexual misconduct allegations.

The university said that, last year, 38 women reported to the University of Virginia that they were sexually assaulted by another student, but only nine opted for a formal investigation, and only four stuck it out.

Advocates: Rolling Stone controversy a distraction from rape problem

Uncertainty about the past -- and the future

Jackie's supporters initially were shocked after the Rolling Stone apology. Some stumbled for the right words. Some said they wanted an explanation.

After a few days, most said they believe something bad did happen on September 28, 2012, the night Rolling Stone reports she was attacked. Yet many also believe it's possible some of the graphic and disturbing details in Rolling Stone were wrong.

Sarah Roderick, a student who knows Jackie, said Jackie was terrified before the Rolling Stone article because she feared the retaliation. She acknowledged that "there do appear to be holes in her story" but said few rape victims give "a straight linear account" of their attack.

Another friend and peer advocate, Annie Forrest, said that, after the apology, Jackie was overwhelmed and that she never expected the fallout to be so bad. Forrest said the account Jackie gave to Rolling Stone is consistent with what Jackie told her about the incident.

Meanwhile, as investigators try to sort out varying versions of events, unanswered questions swirl around campus and beyond, as students start a month-long winter break.

Jackie has not spoken publicly since Rolling Stone published its story. Her lawyer recently told the news media that Jackie would like some privacy.

Next month, when classes resume, life could look a little more normal. Greek life will no longer be suspended. Barring major updates, TV news vans should be out of the much-coveted parking spots.

Students, many unsure exactly what to think, hope for a much less eventful new year.

Report: Non-student females face more sexual assault than students