1960s photojournalists showed the world some of the most dramatic moments of the Vietnam War through their camera lenses. LIFE magazine's Larry Burrows photographed wounded Marine Gunnery Sgt. Jeremiah Purdie, center, reaching toward a stricken soldier after a firefight south of the Demilitarized Zone in Vietnam in 1966. Commonly known as Reaching Out, Burrows shows us tenderness and terror all in one frame. According to LIFE, the magazine did not publish the picture until five years later to commemorate Burrows, who was killed with AP photographer Henri Huet and three other photographers in Laos.

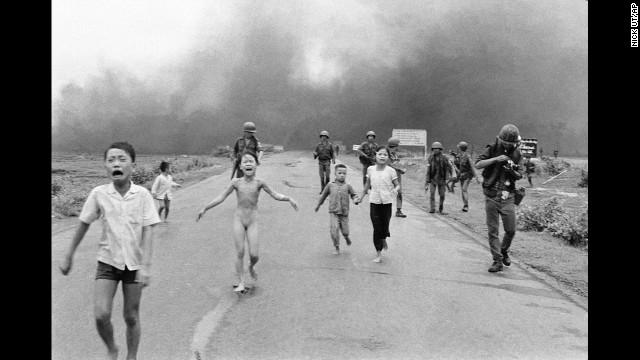

1960s photojournalists showed the world some of the most dramatic moments of the Vietnam War through their camera lenses. LIFE magazine's Larry Burrows photographed wounded Marine Gunnery Sgt. Jeremiah Purdie, center, reaching toward a stricken soldier after a firefight south of the Demilitarized Zone in Vietnam in 1966. Commonly known as Reaching Out, Burrows shows us tenderness and terror all in one frame. According to LIFE, the magazine did not publish the picture until five years later to commemorate Burrows, who was killed with AP photographer Henri Huet and three other photographers in Laos.  Associated Press photographer Nick Ut photographed terrified children running from the site of a Vietnam napalm attack in 1972. A South Vietnamese plane accidentally dropped napalm on its own troops and civilians. Nine-year-old Kim Phuc, center, ripped off her burning clothes while she ran. The image communicated the horrors of the war and contributed to growing U.S. anti-war sentiment. After taking the photograph, Ut took the children to a Saigon hospital.

Associated Press photographer Nick Ut photographed terrified children running from the site of a Vietnam napalm attack in 1972. A South Vietnamese plane accidentally dropped napalm on its own troops and civilians. Nine-year-old Kim Phuc, center, ripped off her burning clothes while she ran. The image communicated the horrors of the war and contributed to growing U.S. anti-war sentiment. After taking the photograph, Ut took the children to a Saigon hospital.  Eddie Adams photographed South Vietnamese police chief Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan killing Viet Cong suspect Nguyen Van Lem in Saigon in 1968. Adams later regretted the impact of the Pulitzer Prize-winning image, apologizing to Gen. Nguyen and his family. "I'm not saying what he did was right," Adams wrote in Time magazine, "but you have to put yourself in his position."

Eddie Adams photographed South Vietnamese police chief Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan killing Viet Cong suspect Nguyen Van Lem in Saigon in 1968. Adams later regretted the impact of the Pulitzer Prize-winning image, apologizing to Gen. Nguyen and his family. "I'm not saying what he did was right," Adams wrote in Time magazine, "but you have to put yourself in his position."  A helicopter raises the body of an American paratrooper killed in action in the jungle near the Cambodian border in 1966. Henri Huet, a French war photographer covering the war for the Associated Press, captured some of the most influential images of the war. Huet died along with LIFE photographer Larry Burrows and three other photographers when their helicopter was shot down over Laos in 1971.

A helicopter raises the body of an American paratrooper killed in action in the jungle near the Cambodian border in 1966. Henri Huet, a French war photographer covering the war for the Associated Press, captured some of the most influential images of the war. Huet died along with LIFE photographer Larry Burrows and three other photographers when their helicopter was shot down over Laos in 1971.  Legendary Welsh war photographer Philip Jones Griffiths captured the battle for Saigon in 1968. U.S. policy in Vietnam was based on the premise that peasants driven into the towns and cities by the carpet-bombing of the countryside would be safe. Furthermore, removed from their traditional value system, they could be prepared for imposition of consumerism. This "restructuring" of society suffered a setback when, in 1968, death rained down on the urban enclaves. In 1971 Griffiths published "Vietnam Inc." and it became one of the most sought after photography books.

Legendary Welsh war photographer Philip Jones Griffiths captured the battle for Saigon in 1968. U.S. policy in Vietnam was based on the premise that peasants driven into the towns and cities by the carpet-bombing of the countryside would be safe. Furthermore, removed from their traditional value system, they could be prepared for imposition of consumerism. This "restructuring" of society suffered a setback when, in 1968, death rained down on the urban enclaves. In 1971 Griffiths published "Vietnam Inc." and it became one of the most sought after photography books.  Newly freed U.S. prisoner of war Air Force Lt. Col. Robert L. Stirm is greeted by his family at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, California, in 1973. This Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph, named Burst of Joy, was taken by Associated Press photographer Sal Veder. "You could feel the energy and the raw emotion in the air," Veder told Smithsonian Magazine in 2005.

Newly freed U.S. prisoner of war Air Force Lt. Col. Robert L. Stirm is greeted by his family at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, California, in 1973. This Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph, named Burst of Joy, was taken by Associated Press photographer Sal Veder. "You could feel the energy and the raw emotion in the air," Veder told Smithsonian Magazine in 2005.  This 1965 photo by Horst Faas shows U.S. helicopters protecting South Vietnamese troops northwest of Saigon. As the Associated Press chief photographer for Southeast Asia from 1962-1974, Faas earned two Pulitzer Prizes.

This 1965 photo by Horst Faas shows U.S. helicopters protecting South Vietnamese troops northwest of Saigon. As the Associated Press chief photographer for Southeast Asia from 1962-1974, Faas earned two Pulitzer Prizes.  Oliver Noonan, a former photographer with the Boston Globe, captured this image of American soldiers listening to a radio broadcast in Vietnam in 1966. Noonan took leave from Boston to work in Vietnam for the Associated Press. He died when his helicopter was shot down near Da Nang in August 1969.

Oliver Noonan, a former photographer with the Boston Globe, captured this image of American soldiers listening to a radio broadcast in Vietnam in 1966. Noonan took leave from Boston to work in Vietnam for the Associated Press. He died when his helicopter was shot down near Da Nang in August 1969.  In June 1963, photographer Malcolm Browne showed the world a shocking display of protest. A Buddhist monk named Thich Quang Duc burned himself to death on a street in Saigon to protest alleged persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government. The image won Browne the World Press Photo of the Year.

In June 1963, photographer Malcolm Browne showed the world a shocking display of protest. A Buddhist monk named Thich Quang Duc burned himself to death on a street in Saigon to protest alleged persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government. The image won Browne the World Press Photo of the Year.  Tim Page photographed a U.S. helicopter taking off from a clearing near Du Co SF camp in Vietnam in 1965. Wounded soldiers crouch in the dust of the departing helicopter. The military convoy was on its way to relieve the camp when it was ambushed.

Tim Page photographed a U.S. helicopter taking off from a clearing near Du Co SF camp in Vietnam in 1965. Wounded soldiers crouch in the dust of the departing helicopter. The military convoy was on its way to relieve the camp when it was ambushed.  Frenchman Marc Riboud captured one of the most well-known anti-war images in 1967. Jan Rose Kasmir confronts National Guard troops outside the Pentagon during a protest march. The photo helped turn public opinion against the war. "She was just talking, trying to catch the eye of the soldiers, maybe try to have a dialogue with them," recalled Riboud in the April 2004 Smithsonian magazine, "I had the feeling the soldiers were more afraid of her than she was of the bayonets."

Frenchman Marc Riboud captured one of the most well-known anti-war images in 1967. Jan Rose Kasmir confronts National Guard troops outside the Pentagon during a protest march. The photo helped turn public opinion against the war. "She was just talking, trying to catch the eye of the soldiers, maybe try to have a dialogue with them," recalled Riboud in the April 2004 Smithsonian magazine, "I had the feeling the soldiers were more afraid of her than she was of the bayonets."  In this 1965 Henri Huet photograph, Chaplain John McNamara administers last rites to photographer Dickey Chapelle in South Vietnam. Chapelle was covering a U.S. Marine unit near Chu Lai for the National Observer when a mine seriously wounded her and four Marines. Chappelle died en route to a hospital, the first American woman correspondent ever killed in action.

In this 1965 Henri Huet photograph, Chaplain John McNamara administers last rites to photographer Dickey Chapelle in South Vietnam. Chapelle was covering a U.S. Marine unit near Chu Lai for the National Observer when a mine seriously wounded her and four Marines. Chappelle died en route to a hospital, the first American woman correspondent ever killed in action.  Mary Ann Vecchio screams as she kneels over Jeffrey Miller's body during the deadly anti-war demonstration at Kent State University in 1970. Student photographer John Filo captured the Pulitzer Prize-winning image after Ohio National Guardsmen fired into a crowd of protesters, killing four students and wounding nine others. An editor manipulated a version of the image to remove the fence post above Vecchio's head, sparking controversy.

Mary Ann Vecchio screams as she kneels over Jeffrey Miller's body during the deadly anti-war demonstration at Kent State University in 1970. Student photographer John Filo captured the Pulitzer Prize-winning image after Ohio National Guardsmen fired into a crowd of protesters, killing four students and wounding nine others. An editor manipulated a version of the image to remove the fence post above Vecchio's head, sparking controversy.  For his dramatic photographs of the Vietnam War, United Press International staff photographer David Hume Kennerly won the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography. This 1971 photo from Kennerly's award-winning portfolio shows an American GI, his weapon drawn, cautiously moving over a devastated hill near Firebase Gladiator.

For his dramatic photographs of the Vietnam War, United Press International staff photographer David Hume Kennerly won the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography. This 1971 photo from Kennerly's award-winning portfolio shows an American GI, his weapon drawn, cautiously moving over a devastated hill near Firebase Gladiator.  Hubert Van Es, a Dutch photojournalist working at the offices of United Press International, took this photo on April 29, 1975, of a CIA employee helping evacuees onto an Air America helicopter. It became one of the best known images of the U.S. evacuation of Saigon. Van Es never received royalties for the UPI-owned photo. The rights are owned by Bill Gates through his company, Corbis.

Hubert Van Es, a Dutch photojournalist working at the offices of United Press International, took this photo on April 29, 1975, of a CIA employee helping evacuees onto an Air America helicopter. It became one of the best known images of the U.S. evacuation of Saigon. Van Es never received royalties for the UPI-owned photo. The rights are owned by Bill Gates through his company, Corbis.  Associated Press photographer Art Greenspon captured this photo of soldiers aiding wounded comrades. The first sergeant of A Company, 101st Airborne Division, guided a medevac helicopter through the jungle to retrieve casualties near Hue in April 1968.

Associated Press photographer Art Greenspon captured this photo of soldiers aiding wounded comrades. The first sergeant of A Company, 101st Airborne Division, guided a medevac helicopter through the jungle to retrieve casualties near Hue in April 1968.

- Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel has directed the Pentagon to reassess Vietnam era discharges

- The move could allow veterans who were never diagnosed with PTSD the ability to claim some benefits

- Homelessness and suicide among Vietnam veterans has led to calls for change

Editor's note: Barbara Starr's interview with Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel will air Tuesday, Nov. 11, on CNN's The Situation Room

Washington (CNN) -- Memories of his own service in Vietnam and the destructive nature of combat are never far from the mind of Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel, the first former enlisted man to lead the Pentagon.

"Every Vietnam veteran understands," Hagel told CNN's Barbara Starr during an interview outside his office in the Pentagon. "Any veteran who has ever served in a war understands that, and I think we should never forget the consequences of war."

Decades after the U.S. conflict in Vietnam, Hagel is using the power of his office to help some of the most troubled veterans of that war get the second chance he feels some deserve.

He is essentially ordering the Pentagon to open the books and allow some veterans of that war with less than honorable discharges to be classified as suffering from post traumatic stress and allow that to be a considered factor in their discharge.

Related: Chuck Hagel reunites with Vietnam platoon commander

Biden lays wreath for Veterans Day

Biden lays wreath for Veterans Day The move could allow veterans who never qualified for disability pay because of their discharge status to finally be compensated.

For Hagel, who served as a senior official in the Veterans Department during the early years of the Reagan administration, the time has come to address an issue overshadowing veterans of his war, that has really only come to the forefront recent years.

"I just really felt, as I always have, that they deserve a little break here lets take another look," Hagel said of the policy change. "I think a lot of people were treated unfairly because there was no recognition of PTSD."

It is a recognition that many feel is long overdue.

FLOTUS Talks Unemployment for Women Vets

FLOTUS Talks Unemployment for Women Vets "In our generation, there was the term the 'crazy' Vietnam vet," Steve Peck, a former Marine who fought in Vietnam, said recently. "You know, guys shooting up gas stations, and robbing stores, and, you know, going off and killing people. That was the impression of Vietnam veterans when they came back."

Peck has spent his career advocating for veterans of that war and trying to shine a light on a mental condition that was not recognized and may have unfairly penalized some of those who came home.

"It was just seen an as aberration, it was not seen as something that was a natural result of being in combat, and that's why so many Vietnam vets are so alienated," Peck said.

With most Vietnam vets now in their sixties and seventies, time is a precious commodity. And with high rates of homelessness, depression and suicide among the group, the drumbeat for this recognition has grown louder.

Veteran honors friend through stargazing

Veteran honors friend through stargazing CNN visited a facility in Long Beach, California taking care of more than 500 homeless veterans, many of them from Vietnam who are still struggling from that long ago war.

"I used to have nightmares when I came home and pretty much blocked it out of my mind," said Joel Hunt, a resident of the facility who was sent to Vietnam when he was 19.

He is glad the government is looking to do more for some of his buddies.

"I think it's great because you know we were drafted, we were forced to go," he said.

Some forty years later, the man who runs the Pentagon, fully understands the challenges his fellow veterans faced after coming home.

"No one was ever told about what you would be dealing with or any kind of reaction to war, or the horrors of war," Hagel said.

And with the job, came an opportunity to address an oversight affecting many of his fellow veterans

"I think it's a responsibility I have," Hagel said. "I think that any Vietnam veteran who had the privilege of holding this job that I have would do the same thing, and I just think it's an obligation I have to those I served with."