- NEW: Doctor who survived Ebola says: "It is a fire straight from the pit of hell"

- Obama says "the world is looking to" the U.S. for leadership on Ebola

- U.S. personnel in West Africa could increase by 3,000

- Obama to call on Congress to approve $88 million more

(CNN) -- After an in-person briefing from the staff at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, President Barack Obama on Tuesday announced a "major increase" in the U.S. response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

The United States will send troops, material to build field hospitals, additional health care workers, community care kits and badly needed medical supplies.

Countless taxis filled with families worried they've become infected with Ebola currently crisscross Monrovia in search of help.

They scour the Liberian capital, but not one clinic can take them in for treatment.

Obama: Ebola threat could become 'global'

Obama: Ebola threat could become 'global'  WHO: West Africa can't keep up with Ebola

WHO: West Africa can't keep up with Ebola  'Not 1 bed' available for Ebola patients

'Not 1 bed' available for Ebola patients

Health workers in Monrovia, Liberia, move the body of a person who they suspect died from the Ebola virus on Tuesday, September 16. Health officials say the Ebola outbreak in West Africa is the deadliest ever. More than 4,700 cases have been reported since December, with more than 2,400 of them ending in fatalities, according to the World Health Organization.

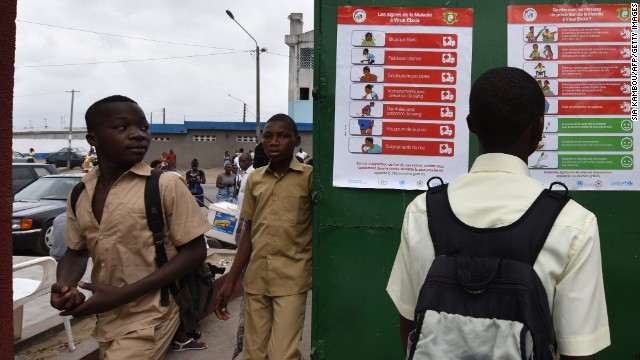

Health workers in Monrovia, Liberia, move the body of a person who they suspect died from the Ebola virus on Tuesday, September 16. Health officials say the Ebola outbreak in West Africa is the deadliest ever. More than 4,700 cases have been reported since December, with more than 2,400 of them ending in fatalities, according to the World Health Organization.  A student of the Sainte Therese school in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, looks at placards Monday, September 15, that were put up to raise awareness about the symptoms of the Ebola virus.

A student of the Sainte Therese school in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, looks at placards Monday, September 15, that were put up to raise awareness about the symptoms of the Ebola virus.  Boxes of aid, donated by Ghana's President and the chairman of the Economic Community Of West African States, sit in an airport in Conakry, Guinea, on September 15.

Boxes of aid, donated by Ghana's President and the chairman of the Economic Community Of West African States, sit in an airport in Conakry, Guinea, on September 15.  Members of a volunteer medical team wear protective gear before the burying of an Ebola victim Saturday, September 13, in Conakry.

Members of a volunteer medical team wear protective gear before the burying of an Ebola victim Saturday, September 13, in Conakry.  A child stops on a Monrovia street Friday, September 12, to look at a man who is suspected of suffering from Ebola.

A child stops on a Monrovia street Friday, September 12, to look at a man who is suspected of suffering from Ebola.  Health workers on Wednesday, September 10, carry the body of a woman who they suspect died from the Ebola virus in Monrovia.

Health workers on Wednesday, September 10, carry the body of a woman who they suspect died from the Ebola virus in Monrovia.  A woman in Monrovia carries the belongings of her husband, who died after he was infected by the Ebola virus.

A woman in Monrovia carries the belongings of her husband, who died after he was infected by the Ebola virus.  Five ambulances that were donated by the United States to help combat the Ebola virus are lined up in Freetown, Sierra Leone, on September 10 following a ceremony that was attended by Sierra Leone President Ernest Bai Koroma.

Five ambulances that were donated by the United States to help combat the Ebola virus are lined up in Freetown, Sierra Leone, on September 10 following a ceremony that was attended by Sierra Leone President Ernest Bai Koroma.  A health worker wears protective gear Sunday, September 7, at ELWA Hospital in Monrovia.

A health worker wears protective gear Sunday, September 7, at ELWA Hospital in Monrovia.  An ambulance transporting Dr. Rick Sacra, an American missionary who was infected with Ebola in Liberia, arrives at the Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska, on Friday, September 5. Sacra was being treated in the hospital's special isolation unit.

An ambulance transporting Dr. Rick Sacra, an American missionary who was infected with Ebola in Liberia, arrives at the Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska, on Friday, September 5. Sacra was being treated in the hospital's special isolation unit.  Medical workers from the Liberian Red Cross carry the body of an Ebola victim Thursday, September 4, in Banjol, Liberia.

Medical workers from the Liberian Red Cross carry the body of an Ebola victim Thursday, September 4, in Banjol, Liberia.  Health workers in Monrovia place a corpse into a body bag on September 4.

Health workers in Monrovia place a corpse into a body bag on September 4.  A rally against the Ebola virus is held in Abidjan on September 4.

A rally against the Ebola virus is held in Abidjan on September 4.  After an Ebola case was confirmed in Senegal, people load cars with household items as they prepare to cross into Guinea from the border town of Diaobe, Senegal, on Wednesday, September 3. Senegal has since closed its borders.

After an Ebola case was confirmed in Senegal, people load cars with household items as they prepare to cross into Guinea from the border town of Diaobe, Senegal, on Wednesday, September 3. Senegal has since closed its borders.  Crowds cheer and celebrate in the streets Saturday, August 30, after Liberian authorities reopened the West Point slum in Monrovia. The military had been enforcing a quarantine on West Point, fearing a spread of the Ebola virus.

Crowds cheer and celebrate in the streets Saturday, August 30, after Liberian authorities reopened the West Point slum in Monrovia. The military had been enforcing a quarantine on West Point, fearing a spread of the Ebola virus.  A ambulance leaves the University Hospital Fann in Dakar, Senegal, where a man was being treated for symptoms of the Ebola virus on Friday, August 29.

A ambulance leaves the University Hospital Fann in Dakar, Senegal, where a man was being treated for symptoms of the Ebola virus on Friday, August 29.  A health worker wearing a protective suit conducts an Ebola prevention drill at the port in Monrovia on August 29.

A health worker wearing a protective suit conducts an Ebola prevention drill at the port in Monrovia on August 29.  Senegalese Health Minister Awa Marie Coll-Seck gives a news conference August 29 to confirm the first case of Ebola in Senegal. She announced that a young Guinean had tested positive for the deadly virus.

Senegalese Health Minister Awa Marie Coll-Seck gives a news conference August 29 to confirm the first case of Ebola in Senegal. She announced that a young Guinean had tested positive for the deadly virus.  Volunteers working with the bodies of Ebola victims in Kenema, Sierra Leone, sterilize their uniforms on Sunday, August 24.

Volunteers working with the bodies of Ebola victims in Kenema, Sierra Leone, sterilize their uniforms on Sunday, August 24.  A Liberian health worker checks people for symptoms of Ebola at a checkpoint near the international airport in Dolo Town, Liberia, on August 24.

A Liberian health worker checks people for symptoms of Ebola at a checkpoint near the international airport in Dolo Town, Liberia, on August 24.  A guard stands at a checkpoint Saturday, August 23, between the quarantined cities of Kenema and Kailahun in Sierra Leone.

A guard stands at a checkpoint Saturday, August 23, between the quarantined cities of Kenema and Kailahun in Sierra Leone.  A burial team from the Liberian Ministry of Health unloads bodies of Ebola victims onto a funeral pyre at a crematorium in Marshall, Liberia, on Friday, August 22.

A burial team from the Liberian Ministry of Health unloads bodies of Ebola victims onto a funeral pyre at a crematorium in Marshall, Liberia, on Friday, August 22.  A humanitarian group worker, right, throws water in a small bag to West Point residents behind the fence of a holding area on August 22. Residents of the quarantined Monrovia slum were waiting for a second consignment of food from the Liberian government.

A humanitarian group worker, right, throws water in a small bag to West Point residents behind the fence of a holding area on August 22. Residents of the quarantined Monrovia slum were waiting for a second consignment of food from the Liberian government.  Dr. Kent Brantly leaves Emory University Hospital on Thursday, August 21, after being declared no longer infectious from the Ebola virus. Brantly was one of two American missionaries brought to Emory for treatment of the deadly virus.

Dr. Kent Brantly leaves Emory University Hospital on Thursday, August 21, after being declared no longer infectious from the Ebola virus. Brantly was one of two American missionaries brought to Emory for treatment of the deadly virus.  Brantly, right, hugs a member of the Emory University Hospital staff after being released from treatment in Atlanta.

Brantly, right, hugs a member of the Emory University Hospital staff after being released from treatment in Atlanta.  Family members of West Point district commissioner Miata Flowers flee the slum in Monrovia while being escorted by the Ebola Task Force on Wednesday, August 20.

Family members of West Point district commissioner Miata Flowers flee the slum in Monrovia while being escorted by the Ebola Task Force on Wednesday, August 20.  An Ebola Task Force soldier beats a local resident while enforcing a quarantine on the West Point slum on August 20.

An Ebola Task Force soldier beats a local resident while enforcing a quarantine on the West Point slum on August 20.  Local residents gather around a very sick Saah Exco, 10, in a back alley of the West Point slum on Tuesday, August 19. The boy was one of the patients that was pulled out of a holding center for suspected Ebola patients after the facility was overrun and closed by a mob on August 16. A local clinic then refused to treat Saah, according to residents, because of the danger of infection. Although he was never tested for Ebola, Saah's mother and brother died in the holding center.

Local residents gather around a very sick Saah Exco, 10, in a back alley of the West Point slum on Tuesday, August 19. The boy was one of the patients that was pulled out of a holding center for suspected Ebola patients after the facility was overrun and closed by a mob on August 16. A local clinic then refused to treat Saah, according to residents, because of the danger of infection. Although he was never tested for Ebola, Saah's mother and brother died in the holding center.  A burial team wearing protective clothing retrieves the body of a 60-year-old Ebola victim from his home near Monrovia on Sunday, August 17.

A burial team wearing protective clothing retrieves the body of a 60-year-old Ebola victim from his home near Monrovia on Sunday, August 17.  lija Siafa, 6, stands in the rain with his 10-year-old sister, Josephine, while waiting outside Doctors Without Borders' Ebola treatment center in Monrovia on August 17. The newly built facility will initially have 120 beds, making it the largest-ever facility for Ebola treatment and isolation.

lija Siafa, 6, stands in the rain with his 10-year-old sister, Josephine, while waiting outside Doctors Without Borders' Ebola treatment center in Monrovia on August 17. The newly built facility will initially have 120 beds, making it the largest-ever facility for Ebola treatment and isolation.  Brett Adamson, a staff member from Doctors Without Borders, hands out water to sick Liberians hoping to enter the new Ebola treatment center on August 17.

Brett Adamson, a staff member from Doctors Without Borders, hands out water to sick Liberians hoping to enter the new Ebola treatment center on August 17.  Workers prepare the new Ebola treatment center on August 17.

Workers prepare the new Ebola treatment center on August 17.  A body, reportedly a victim of Ebola, lies on a street corner in Monrovia on Saturday, August 16.

A body, reportedly a victim of Ebola, lies on a street corner in Monrovia on Saturday, August 16.  Liberian police depart after firing shots in the air while trying to protect an Ebola burial team in the West Point slum of Monrovia on August 16. A crowd of several hundred local residents reportedly drove away the burial team and their police escort. The mob then forced open an Ebola isolation ward and took patients out, saying the Ebola epidemic is a hoax.

Liberian police depart after firing shots in the air while trying to protect an Ebola burial team in the West Point slum of Monrovia on August 16. A crowd of several hundred local residents reportedly drove away the burial team and their police escort. The mob then forced open an Ebola isolation ward and took patients out, saying the Ebola epidemic is a hoax.  A crowd enters the grounds of an Ebola isolation center in the West Point slum on August 16. The mob was reportedly shouting, "No Ebola in West Point."

A crowd enters the grounds of an Ebola isolation center in the West Point slum on August 16. The mob was reportedly shouting, "No Ebola in West Point."  A health worker disinfects a corpse after a man died in a classroom being used as an Ebola isolation ward Friday, August 15, in Monrovia.

A health worker disinfects a corpse after a man died in a classroom being used as an Ebola isolation ward Friday, August 15, in Monrovia.  A boy tries to prepare his father before they are taken to an Ebola isolation ward August 15 in Monrovia.

A boy tries to prepare his father before they are taken to an Ebola isolation ward August 15 in Monrovia.  Kenyan health officials take passengers' temperature as they arrive at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport on Thursday, August 14, in Nairobi, Kenya.

Kenyan health officials take passengers' temperature as they arrive at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport on Thursday, August 14, in Nairobi, Kenya.  A hearse carries the coffin of Spanish priest Miguel Pajares after he died at a Madrid hospital on Tuesday, August 12. Pajares, 75, contracted Ebola while he was working as a missionary in Liberia.

A hearse carries the coffin of Spanish priest Miguel Pajares after he died at a Madrid hospital on Tuesday, August 12. Pajares, 75, contracted Ebola while he was working as a missionary in Liberia.  A member of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention leads a training session on Ebola infection control Monday, August 11, in Lagos, Nigeria.

A member of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention leads a training session on Ebola infection control Monday, August 11, in Lagos, Nigeria.  Health workers in Kenema, Sierra Leone, screen people for the Ebola virus on Saturday, August 9, before they enter the Kenema Government Hospital.

Health workers in Kenema, Sierra Leone, screen people for the Ebola virus on Saturday, August 9, before they enter the Kenema Government Hospital.  A health worker at the Kenema Government Hospital carries equipment used to decontaminate clothing and equipment on August 9.

A health worker at the Kenema Government Hospital carries equipment used to decontaminate clothing and equipment on August 9.  Health care workers wear protective gear at the Kenema Government Hospital on August 9.

Health care workers wear protective gear at the Kenema Government Hospital on August 9.  Paramedics in protective suits move Pajares, the infected Spanish priest, at Carlos III Hospital in Madrid on Thursday, August 7. He died five days later.

Paramedics in protective suits move Pajares, the infected Spanish priest, at Carlos III Hospital in Madrid on Thursday, August 7. He died five days later.  Nurses carry the body of an Ebola victim from a house outside Monrovia on Wednesday, August 6.

Nurses carry the body of an Ebola victim from a house outside Monrovia on Wednesday, August 6.  A Nigerian health official wears protective gear August 6 at Murtala Muhammed International Airport in Lagos.

A Nigerian health official wears protective gear August 6 at Murtala Muhammed International Airport in Lagos.  Officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta sit in on a conference call about Ebola with CDC team members deployed in West Africa on Tuesday, August 5.

Officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta sit in on a conference call about Ebola with CDC team members deployed in West Africa on Tuesday, August 5.  Aid worker Nancy Writebol, wearing a protective suit, gets wheeled on a gurney into Emory University Hospital in Atlanta on August 5. A medical plane flew Writebol from Liberia to the United States after she and her colleague Dr. Kent Brantly were infected with the Ebola virus in the West African country.

Aid worker Nancy Writebol, wearing a protective suit, gets wheeled on a gurney into Emory University Hospital in Atlanta on August 5. A medical plane flew Writebol from Liberia to the United States after she and her colleague Dr. Kent Brantly were infected with the Ebola virus in the West African country.  Nigerian health officials are on hand to screen passengers at Murtala Muhammed International Airport on Monday, August 4.

Nigerian health officials are on hand to screen passengers at Murtala Muhammed International Airport on Monday, August 4.  A man gets sprayed with disinfectant Sunday, August 3, in Monrovia.

A man gets sprayed with disinfectant Sunday, August 3, in Monrovia.  Dr. Kent Brantly, right, gets out of an ambulance after arriving at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta on Saturday, August 2. Brantly was infected with the Ebola virus in Africa, but he was brought back to the United States for further treatment.

Dr. Kent Brantly, right, gets out of an ambulance after arriving at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta on Saturday, August 2. Brantly was infected with the Ebola virus in Africa, but he was brought back to the United States for further treatment.  Nurses wearing protective clothing are sprayed with disinfectant Friday, August 1, in Monrovia after they prepared the bodies of Ebola victims for burial.

Nurses wearing protective clothing are sprayed with disinfectant Friday, August 1, in Monrovia after they prepared the bodies of Ebola victims for burial.  A nurse disinfects the waiting area at the ELWA Hospital in Monrovia on Monday, July 28.

A nurse disinfects the waiting area at the ELWA Hospital in Monrovia on Monday, July 28.  Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, right, walks past an Ebola awareness poster in downtown Monrovia as Liberia marked the 167th anniversary of its independence Saturday, July 26. The Liberian government dedicated the anniversary to fighting the deadly disease.

Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, right, walks past an Ebola awareness poster in downtown Monrovia as Liberia marked the 167th anniversary of its independence Saturday, July 26. The Liberian government dedicated the anniversary to fighting the deadly disease.  In this photo provided by Samaritan's Purse, Dr. Kent Brantly, left, treats an Ebola patient in Monrovia. On July 26, the North Carolina-based group said Brantly tested positive for the disease. Days later, Brantly arrived in Georgia to be treated at an Atlanta hospital, becoming the first Ebola patient to knowingly be treated in the United States.

In this photo provided by Samaritan's Purse, Dr. Kent Brantly, left, treats an Ebola patient in Monrovia. On July 26, the North Carolina-based group said Brantly tested positive for the disease. Days later, Brantly arrived in Georgia to be treated at an Atlanta hospital, becoming the first Ebola patient to knowingly be treated in the United States.  A 10-year-old boy whose mother was killed by the Ebola virus walks with a doctor from the aid organization Samaritan's Purse after being taken out of quarantine Thursday, July 24, in Monrovia.

A 10-year-old boy whose mother was killed by the Ebola virus walks with a doctor from the aid organization Samaritan's Purse after being taken out of quarantine Thursday, July 24, in Monrovia.  A doctor puts on protective gear at the treatment center in Kailahun, Sierra Leone, on Sunday, July 20.

A doctor puts on protective gear at the treatment center in Kailahun, Sierra Leone, on Sunday, July 20.  Members of Doctors Without Borders adjust tents in the isolation area in Kailahun on July 20.

Members of Doctors Without Borders adjust tents in the isolation area in Kailahun on July 20.  Boots dry in the Ebola treatment center in Kailahun on July 20.

Boots dry in the Ebola treatment center in Kailahun on July 20.  Red Cross volunteers prepare to enter a house where an Ebola victim died in Pendembu, Sierra Leone, on Friday, July 18.

Red Cross volunteers prepare to enter a house where an Ebola victim died in Pendembu, Sierra Leone, on Friday, July 18.  Dr. Jose Rovira of the World Health Organization takes a swab from a suspected Ebola victim in Pendembu on July 18.

Dr. Jose Rovira of the World Health Organization takes a swab from a suspected Ebola victim in Pendembu on July 18.  Red Cross volunteers disinfect each other with chlorine after removing the body of an Ebola victim from a house in Pendembu on July 18.

Red Cross volunteers disinfect each other with chlorine after removing the body of an Ebola victim from a house in Pendembu on July 18.  A dressing assistant prepares a Doctors Without Borders member before entering an isolation ward Thursday, July 17, in Kailahun.

A dressing assistant prepares a Doctors Without Borders member before entering an isolation ward Thursday, July 17, in Kailahun.  A doctor works in the field laboratory at the Ebola treatment center in Kailahun on July 17.

A doctor works in the field laboratory at the Ebola treatment center in Kailahun on July 17.  Doctors Without Borders staff prepare to enter the isolation ward at an Ebola treatment center in Kailahun on July 17.

Doctors Without Borders staff prepare to enter the isolation ward at an Ebola treatment center in Kailahun on July 17.  A health worker with disinfectant spray walks down a street outside the government hospital in Kenema on Thursday, July 10.

A health worker with disinfectant spray walks down a street outside the government hospital in Kenema on Thursday, July 10.  Dr. Mohamed Vandi of the Kenema Government Hospital trains community volunteers who will aim to educate people about Ebola in Sierra Leone.

Dr. Mohamed Vandi of the Kenema Government Hospital trains community volunteers who will aim to educate people about Ebola in Sierra Leone.  Police block a road outside Kenema to stop motorists for a body temperature check on Wednesday, July 9.

Police block a road outside Kenema to stop motorists for a body temperature check on Wednesday, July 9.  A woman has her temperature taken at a screening checkpoint on the road out of Kenema on July 9.

A woman has her temperature taken at a screening checkpoint on the road out of Kenema on July 9.  A member of Doctors Without Borders puts on protective gear at the isolation ward of the Donka Hospital in Conakry, Guinea, on Saturday, June 28.

A member of Doctors Without Borders puts on protective gear at the isolation ward of the Donka Hospital in Conakry, Guinea, on Saturday, June 28.  Airport employees check passengers in Conakry before they leave the country on Thursday, April 10.

Airport employees check passengers in Conakry before they leave the country on Thursday, April 10.  CNN's Dr. Sanjay Gupta, left, works in the World Health Organization's mobile lab in Conakry. Gupta traveled to Guinea in April to report on the deadly virus.

CNN's Dr. Sanjay Gupta, left, works in the World Health Organization's mobile lab in Conakry. Gupta traveled to Guinea in April to report on the deadly virus.  A Guinea-Bissau customs official watches arrivals from Conakry on Tuesday, April 8.

A Guinea-Bissau customs official watches arrivals from Conakry on Tuesday, April 8.  Egidia Almeida, a nurse in Guinea-Bissau, scans a Guinean citizen coming from Conakry on April 8.

Egidia Almeida, a nurse in Guinea-Bissau, scans a Guinean citizen coming from Conakry on April 8.  A scientist separates blood cells from plasma cells to isolate any Ebola RNA and test for the virus Thursday, April 3, at the European Mobile Laboratory in Gueckedou, Guinea.

A scientist separates blood cells from plasma cells to isolate any Ebola RNA and test for the virus Thursday, April 3, at the European Mobile Laboratory in Gueckedou, Guinea.  Members of Doctors Without Borders carry a dead body in Gueckedou on Friday, April 1.

Members of Doctors Without Borders carry a dead body in Gueckedou on Friday, April 1.  Gloves and boots used by medical personnel dry in the sun April 1 outside a center for Ebola victims in Gueckedou.

Gloves and boots used by medical personnel dry in the sun April 1 outside a center for Ebola victims in Gueckedou.  A health specialist works Monday, March 31, in a tent laboratory set up at a Doctors Without Borders facility in southern Guinea.

A health specialist works Monday, March 31, in a tent laboratory set up at a Doctors Without Borders facility in southern Guinea.  Health specialists work March 31 at an isolation ward for patients at the facility in southern Guinea.

Health specialists work March 31 at an isolation ward for patients at the facility in southern Guinea.  Workers associated with Doctors Without Borders prepare isolation and treatment areas Friday, March 28, in Guinea.

Workers associated with Doctors Without Borders prepare isolation and treatment areas Friday, March 28, in Guinea. Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Photos: Ebola outbreak in West Africa

Photos: Ebola outbreak in West Africa "Today, there is not one single bed available for the treatment of an Ebola patient in the entire country of Liberia," said Margaret Chan, the World Health Organization's director-general.

"As soon as a new Ebola treatment facility is opened, it immediately fills to overflowing with patients," the WHO said.

Hospitals and clinics in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone -- the countries hit hardest by the outbreak -- are overwhelmed by what the WHO is calling the deadliest Ebola outbreak in history.

Ebola Fast Facts: Everything you need to know

The virus has killed at least 2,400 people, and thousands more are infected. And there are now cases in Nigeria and Senegal.

"The number of new cases is increasing exponentially," the WHO said, calling the situation a "dire emergency with ... unprecedented dimensions of human suffering."

"Men and women and children are just sitting, waiting to die right now," Obama said.

"This is a daunting task, but here's what gives us hope. The world knows how to fight this disease. It's not a mystery. We know the science. We know how to prevent it from spreading. We know how to care for those who contract it. We know that if we take the proper steps, we can save lives. But we have to act fast," Obama said.

"We can't dawdle on this one. We have to move with force and make sure that we are catching this as best we can, given that it has already broken out in ways that we have not seen before."

The CDC already has hundreds of professionals on the ground in what the President described as the "largest international response in the history of the CDC."

Maj. Gen. Darryl Williams, commander of the U.S. Army Africa, arrived in Liberia on Tuesday. Liberian leadership asked that the U.S. military step in to help support civilian efforts there.

Williams will coordinate the military's efforts to improve logistics, to build additional field hospitals and to create what the President called an "air bridge" to bring in additional supplies and health care workers. The effort will be called Operation United Assistance.

The new treatment centers may house up to 1,700 additional beds. American military personnel in the region could increase by 3,000, administration officials said.

The U.S. will also create a new training facility to help prepare thousands more health care workers to handle sick patients. U.S. medics will train up to 500 health care workers per week to identify and care for people with Ebola.

USAID will give 400,000 treatment kits with sanitizer and other protective items like gloves to families to help them protect their own safety as they care for sick relatives.

The President also called on Congress to approve additional funding his administration requested to carry on these critical efforts to stop the virus.

Obama added that "faced with this outbreak, the world is looking to" the United States to lead international efforts to combat the virus. He said the United States is ready to take on that leadership role.

"Here's the hard truth. In West Africa, Ebola is now an epidemic of the likes that we have not seen before. It's spiraling out of control," Obama said. "If the outbreak is not stopped now, we could be looking at hundreds of thousands of people infected with profound political and economic and security implications for all of us."

Washington has already committed more than $100 million to combat Ebola, according to the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Last week, USAID said it would spend $75 million to build treatment facilities and supply them with medical equipment. The Pentagon says it's working to shift $500 million of not yet obligated funds toward the Ebola effort.

Airborne Ebola? A nightmare that could happen

Public health campaigns will be broadcast through existing networks in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea.

'Hundreds turn into thousands'

Doctor 'improving' after Ebola diagnosis

Doctor 'improving' after Ebola diagnosis  Why isn't Ebola containment working?

Why isn't Ebola containment working?  Gates Foundation to donate $50 million

Gates Foundation to donate $50 million The President's visit to the CDC comes amid escalating criticism from health experts of the global response to the outbreak in West Africa.

U.S. officials hope a more coordinated response on the ground, put in place by the United States, will encourage other nations to step up their efforts.

"This is a global threat and demands a global response," Obama said. He added that the international community needs to move faster.

Next week, the U.S. will chair an emergency meeting of the U.N. Security Council to maximize the response to the Ebola crisis. The White House will also bring more countries together to talk about future health threats.

Tuesday, WHO announced that China dispatched a mobile laboratory team to Sierra Leone to help test for the virus. The team of 59 from the Chinese Center for Disease Control includes epidemiologists, clinicians and nurses. This team will join 115 Chinese medical staff already on the ground in Sierra Leone.

Opinion: How not to handle Ebola

Nongovernmental organizations that have been fighting this outbreak since its start reacted positively to Obama's announcement.

"The multifaceted response to the Ebola crisis announced today by President Obama is what we have been hoping for and what is needed in Liberia and West Africa," said Bruce Johnson, president of SIM USA.

Two of the three American workers who contracted Ebola in Liberia and were evacuated to the United States for treatment work for SIM.

SIM and other organizations such as Doctors Without Borders that have been working on the Ebola outbreak since the beginning have been asking for additional international help for months.

"Three things are vital right now: More beds and equipment, more trained medical professionals, and more training of Liberians and West Africans," Johnson said. "This current plan addresses these desperate needs."

One of the doctors who had been working with SIM's clinic in Liberia when he became infected with the virus testified Tuesday in front of a joint hearing in Congress to look at ways to stop Ebola.

Dr. Kent Brantly urged Congress to provide the extra funds to fight the outbreak. Earlier in the day he met with President Obama, who told him about the expanded U.S. efforts.

Brantly said he thanked the President, and urged Congress to back this plan up with "immediate action."

Ebola survivor donates blood to infected American

"As a survivor, it is not only my privilege, but it is my duty to speak out on behalf of the people of West Africa who continue to face unspeakable devastation because of this horrific disease," Brantly said.

He told the story about a patient named Francis who he believes may have been saved had the world acted sooner.

The patient became infected after carrying a neighbor sick with Ebola to a taxi to get him to a hospital.

"If someone had gone alongside Francis and given him a little education and given him the equipment he needed, his family would have a father," Brantly said. Instead his patient died and the world lost "this good Samaritan."

Brantly went on to respond to the analogy some have used to describe Ebola as a fire burning out of control.

He warned, it is a "fire. It is a fire straight from the pit of hell."

"We cannot fool ourselves into thinking that the vast Atlantic Ocean will protect us from the flames of this fire," Brantly said.

Move quickly, he urged, as it is "the only way to keep entire nations from being reduced to ashes."

Could the virus mutate?

There is also a concern about the possibility that the virus could mutate into an even more dangerous form.

Ebola currently transmits only though contact with bodily fluids; a mutation that allows the virus to spread through the air would pose a catastrophic threat to people worldwide, health experts say.

White House press secretary Josh Earnest said Monday that there was still a "very low" likelihood the Ebola virus could mutate in a way that threatens the United States.

Can Sierra Leone's economy survive Ebola?

"Right now, the risk of an Ebola outbreak in the United States is very low," he said, "but that risk would only increase if there were not a robust response on the part of the United States."

The President noted a number of precautionary steps that are being taken in the United States to prevent the disease from spreading here.

The government has stepped up screening at West African airports. It has increased education for flight crews to teach them what to watch for with people who may be sick. It has worked with hospitals and health care workers to prepare them in case there is a domestic Ebola problem.

Will it be enough?

Ebola is more than a health threat to West Africa; it could become a "major humanitarian crisis," according to United Nations Under-Secretary-General Valerie Amos, if it is not stopped soon enough.

The United Nations said that many millions more will be needed to fight the outbreak. U.N. leaders estimate they need $1 billion to fight the epidemic, with about half needed for the worst-hit country, Liberia.

Political systems and infrastructure are fragile in the countries where the virus is concentrated. Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea are still rebuilding their economies after suffering through years of civil wars.

"Now their capacity to deliver the necessities of daily life for their people is on the brink of collapse," Amos said. "The Ebola outbreak poses a serious threat to their post-conflict recovery."

More people are believed to have died in these countries from secondary diseases like malaria and tuberculosis and from chronic illnesses and pregnancies with complications than from Ebola because the health care systems are so strained.

Heavy rain adds to the risk of waterborne diseases like malaria.

Food security has also become a problem. Quarantines keep workers from their jobs and have slowed the delivery of food to certain areas, according to the U.N.

"We must act now if we want to avoid greater humanitarian consequences in future," Amos said.

CNN's Josh Levs, Greg Botelho and Nana Karikari-apau contributed to this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment